| North Luangwa, 1986-1997 |

|

| North Luangwa National Park, Zambia. |

|

| Mark Owens sits with captured poachers and NLNP Game Scouts. |

In 1986, Mark and Delia Owens established the North Luangwa Conservation Project (NLCP) to rehabilitate and conserve the 2,400-square-mile North Luangwa National Park of Zambia. At that time, commercial meat and ivory poachers had killed all of the park's 2,000 black rhinos and they were killing 1,000 of its elephants each year. In the previous decade, poachers had slaughtered up to 100,000 elephants and virtually all of 6,000 black rhinos in the Luangwa Valley as a whole. They set wild fires that burned over 85% of the area every year. If left unprotected, by 1996 North Luangwa would have been sterilized of its large mammals.

The government did not have the resources to adequately protect or develop the park. So Mark and Delia's first priority was to curb poaching by helping improve the efficiency of local game scouts. They provided them with patrol food, camping equipment, trucks, houses, an operations center, training, radio communication, a school for their children, medicines, and cash incentives. After working closely with them for years, the North Luangwa game guards became the best in Zambia.

At the same time, Mark and Delia selected 14 villages located near the park that were notorious for harboring commercial poachers. In fact, poaching was the primary industry in the area, providing more jobs and more sources of protein than any other. So Mark and Delia began NLCP's Community Development Program, establishing small sustainable businesses which provided basic goods and services to the local people and alternative legal jobs to poachers. This program was not a handout. Each business was run as a free enterprise, and the entrepreneur had to repay his initial start-up loan, so that the project could then help others start their own businesses. In this way, NLCP supplanted an illicit economy based on poaching with a legal one, thereby undercutting large-scale commercial poachers who hired hunters and carriers from the villages.

In the past, many villagers traded poached meat for ground maize, their staple diet. NLCP helped them form "wildlife clubs," which used NLCP business loans to purchase and run grinding mills, offering employment to millers, mechanics, and bookkeepers. In some villages these same clubs also used loans to open small general stores, which sold soap, salt, matches, and other basic commodities that people formerly could purchase only by walking days to Mpika and other towns along the main Cape-to-Cairo Road. Villagers also traded poached meat for cooking oil, a much prized commodity in rural Africa. As an alternative, NLCP taught them to grow sunflower seeds and press them for oil using simple hydraulic presses, once again replacing poaching with a sustainable legal trade. Other cottage industries that provided jobs, food, or services to the local people were carpentry shops, fish farms, poultry units, bee keeping, sewing coops, rat trap makers, and cobbler shops. NLCP also assisted subsistence farmers with seed loans, transportation and technical assistance to help them grow protein-rich crops with better yields so they did not have to depend on meat from wild animals. More than 2,000 families in the NLCP target area benefited from NLCP's Community Development and Agricultural Assistance Programs.

|

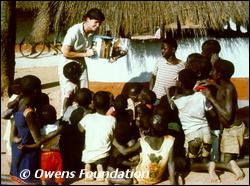

| Delia Owens shows village children their first color picture. |

|

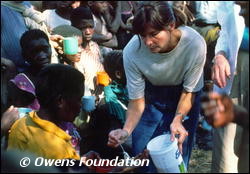

| Delia Owens - Rural Health Demonstration - how to mix "rehydration solution" to treat dehydration. |

Mark and Delia also established the NLCP Conservation Education Program in these same target villages. Many students had never seen a color photograph and schools lacked even the most basic supplies. The NLCP Education Officer visited schools monthly, offering a 500-volume mobile library, curriculum guidelines, school supplies, wildlife slide shows, lectures, and drama competitions, all with a conservation message. Forty-eight American schools participated in a "Sister School Program," a conservation oriented exchange program with NLCP's students exchanging letters, art work, reports, and essays. American schools sent letters, school supplies, books, and donated magazines to their Zambian counterparts. These Zambian students, it is hoped, will not grow up to be poachers.

NLCP's Rural Health Program taught hygiene, first aid, preventive medicine, family planning, and advanced clinical techniques to village medics. NLCP trained and equipped 48 "traditional birth attendants" to assist the pregnant women in the villages near the park. Traditional birth attendants also taught AIDS prevention, early childhood development, and nutrition to the women of their villages.

The ultimate goal of NLCP was to ensure the development of a low-impact tourism industry for the North Luangwa National Park, an industry that would provide employment opportunities and development revenues for villagers who would otherwise depend on NLCP or poaching for their livelihood. Mark and Delia worked with the government to design an enviro-friendly tourism development plan for the park.

The North Luangwa Conservation Project was remarkably successful. When Mark and Delia arrived in 1986, 1,000 elephants were being poached every year. From September of 1994 to May of 1997, not one was killed in the Project area. For the first time in 20 years the elephant population of NLNP increased slightly, and villagers reported elephants, buffalo, hippos, and other large mammals in areas where they have not been seen for two, even three decades. Wildlife research and ecological monitoring documented the recovery of the elephants and other animal populations. Thirty-five elephants were collared with radio transmitters and aircraft were used to chart their range movements, habitat utilization, group size, social structure, and reproductive success.

The people near North Luangwa no longer had to poach, or collaborate with commercial poachers to feed their families. The heads of more than 2,000 families, many of whom were once involved with poaching, had legal, sustainable jobs. Leaders from villages beyond the NLCP area began asking how to start NLCP programs. NLCP has been declared a model for integrated rural development using techniques that involve nonconsumption of wildlife resources.